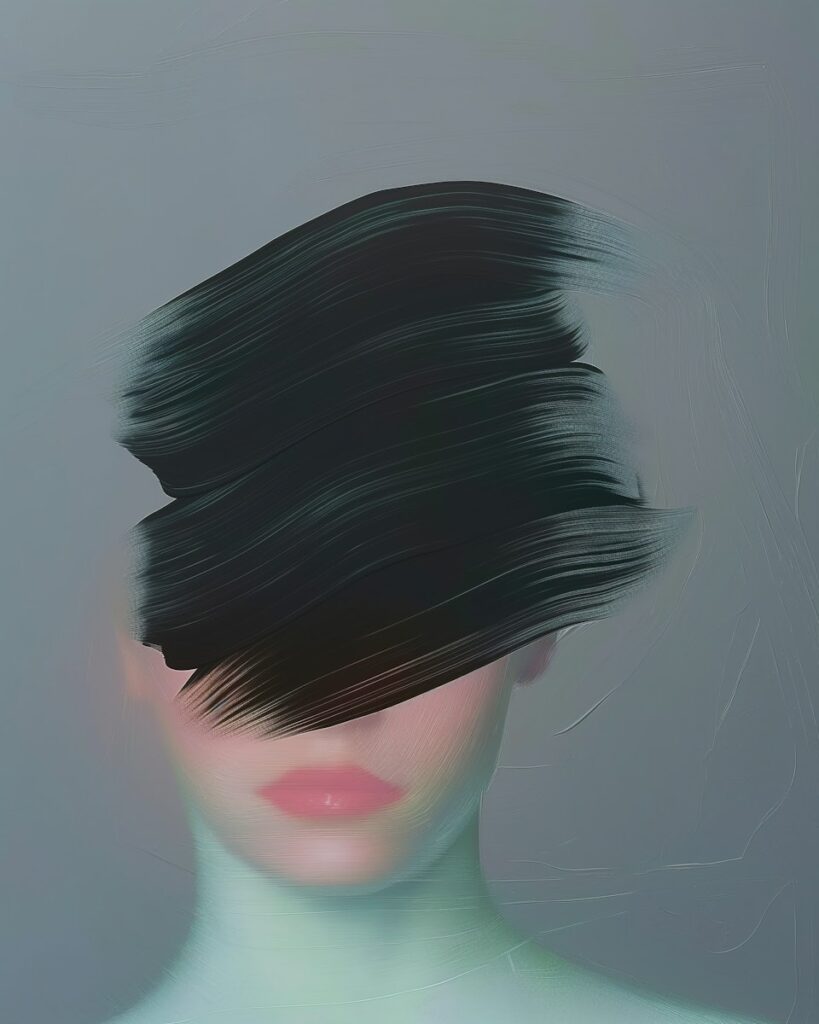

I turn 40 this year. I have three kids, a demanding job, not enough sleep, and an ever-growing list of things to do that somehow never seem to shrink. And when I look in the mirror, all those things stare me back in the face

The tiredness, the fine lines, the evidence of every 2 AM wake-up, every deadline, every moment of stress is etched there on my skin.

And so, I think about Botox.

I think about it when I catch a glimpse of myself in bad lighting, when concealer can no longer disguise the fact that I am exhausted. When I want to feel like the most refreshed version of myself, not the woman who barely scraped together six hours of sleep and ran out the door with coffee she forgot to drink. I don’t want to look different. I just want to look…a little less like I feel.

But then, the voice starts up. Isn’t Botox unfeminist? Isn’t is WRONG?

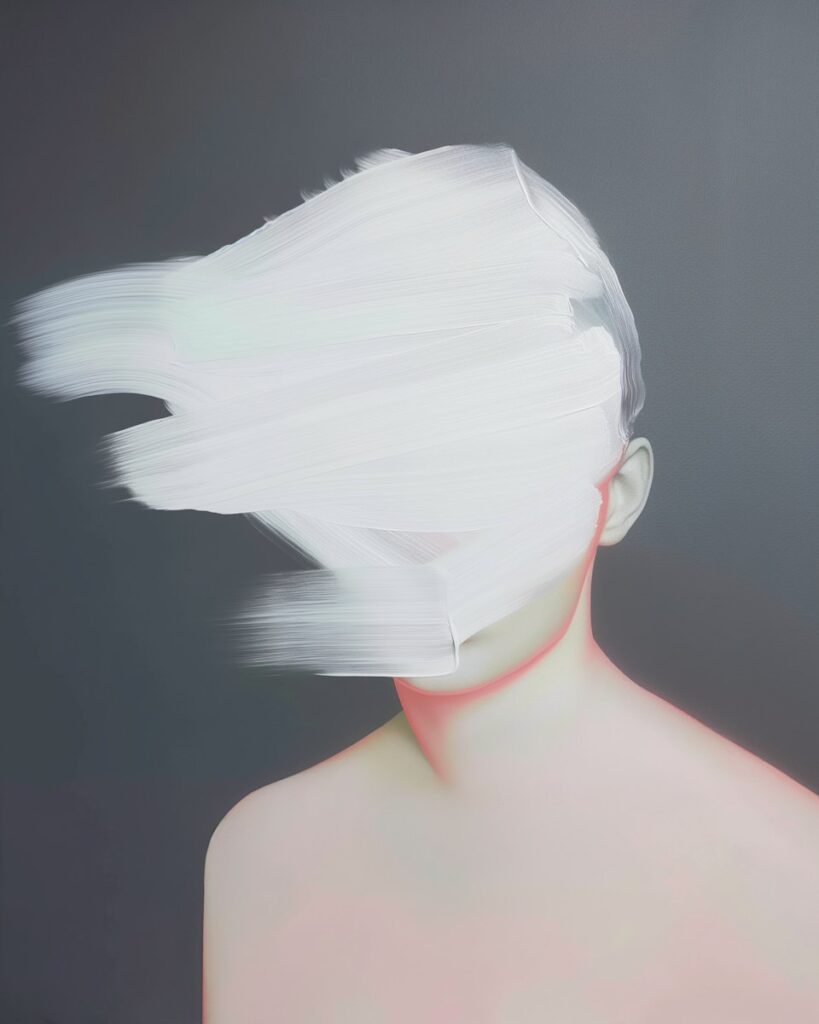

Beauty vs Feminism

I have spent my adult life believing in bodily autonomy, in rejecting unrealistic beauty standards, in embracing the idea that women do not owe the world youth, smooth skin, or looking “refreshed.” I’ve scoffed at celebrities who swear their wrinkle-free faces are thanks to water and a diligent skincare routine. I’ve shaken my head at the way we shame women for aging while simultaneously shaming them for doing anything about it.

And yet, here I am. Thinking about Botox. Googling “how many units for forehead lines?” and quietly calculating how much it costs. I am not immune to the same pressures I rally against.

I tell myself, It’s not about looking younger, it’s about looking well-rested. But isn’t that a slippery slope? Isn’t that the exact branding the beauty industry wants me to buy into—this isn’t anti-aging, it’s just self-care? Am I making an empowered choice for myself, or am I just dressing up internalized beauty standards in a feminist-friendly outfit?

My husband tells me I look beautiful as I am. And yet, it doesn’t erase the way I feel when I see my reflection and notice the way stress has settled into my skin

My husband tells me I look beautiful as I am. He means it. And, though this makes me feel a little like a Darcy-chasing Bridget Jones, I appreciate it.

And yet, it doesn’t erase the way I feel when I see my reflection and notice the way stress has settled into my skin. His love (my husband’s, not Darcy’s, just to be clear) doesn’t change the fact that when I look in the mirror, I want to feel good about what I see. And that, right there, is one of the great contradictions of womanhood—we are told to love ourselves, but also to stay forever appealing to the world around us.

It’s easy to say “age gracefully,” but let’s be honest—graceful aging is a myth when the women who do it best have an entire arsenal of expensive treatments they pretend they don’t use. We celebrate the 50-year-old who looks “incredible for her age” while simultaneously judging the woman who admits she got Botox. So what’s the right move? Pretend we don’t care, or pretend we’re not doing anything to care?

Is Wanting Botox a Betrayal?

I think about my daughter, about the values I want to pass on to her. I want her to know she is enough as she is. That she does not have to shrink, contort, or inject herself into some impossible version of beauty to be worthy.

But then I also think about how Botox is, for some women, simply a tool in their toolkit. Some people wear makeup, some dye their hair, some get fillers, some get facelifts, some do nothing at all. Why should this be the line in the sand?

Perhaps feminism isn’t about whether or not we get Botox—it’s about being honest about why we want it. It’s about acknowledging that the world is unfair to women, that beauty standards are exhausting and often contradictory, and that we are all just trying to navigate it in a way that makes us feel good.

So maybe the answer isn’t whether I should get Botox, but rather: How do I feel about it when I remove the guilt, the judgment, and the weight of external expectations? Maybe the feminist choice isn’t Botox or no Botox—it’s being honest about the fact that we even have to ask ourselves this question in the first place.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough.